The January issue of Pet Business magazine includes a cover article on premium and superpremium pet foods called “A Matter of Trust.” The premise of the article, written by Alyssa Brewer, is perhaps best summed up by this passage:

“With an ever-expanding group of pet owners seeking the healthiest and most nutritious feeding options for their dogs and cats, premium and superpremium diets represent a popular and fast-growing segment. However, the continued success of this category of foods depends on the integrity of the manufacturers and faith on the part of retailers and consumers that these are superior products that are objectively better for their pets.

“Unfortunately, premium and superpremium labels face significant scrutiny and skepticism on multiple fronts.”

Those fronts, Brewer wrote, include doubts (from “industry observers”) about whether label claims on these products match the quality of the products themselves, as well as doubts that benefits promised in the claims, even if true, make much or any difference to pets’ health. Other concerns are the price of the products, which may scare off some consumers, and the continuing influx of products, brands and lines in this growing category making the meaning of premium “murkier” for pet owners and retailers.

I don’t necessarily disagree with any of Brewer’s points, though the term “industry observers” is so vague and amorphous, it’s difficult to know if their views are truly a matter of concern. But in my mind, the continually escalating prices of premium/superpremium pet foods and confusion over exactly what those terms mean—and the two issues are, obviously, connected—represent the chief potential risks to this category and our industry’s overall, long-term health.

It’s no secret that in developed pet food markets, ongoing sales growth over the past several years (definitely since the Great Recession) has come mainly from rising prices and greater sales of higher-priced pet foods, not from a larger volume of pet food being sold. Why is this risky? Listen to the growing chorus of concerns and questions about whether there’s a ceiling to how much “pet parents” will pay for pet food.

For example, Jeremy Petersen, executive vice president of Wild Calling Pet Foods, expressed some trepidation in Pet Nutrition News last year: “We seem to be approaching the point where we are testing the limits of what we can do with new formulas, novel ingredients, etc., and still be at a price point palatable to the consumer. Companies that are innovative and offer products at a price that consumers can find value in will be able to achieve higher prices, but the rate of price appreciation will be far less than in the past.”

Similarly, experts from Packaged Facts who analyze the pet food market have warned that current premiumization tactics may not work forever. “For more than a decade, the strategy of converting pet shoppers to higher-priced fare has paid off handsomely,” wrote David Lummis in the May 2015 issue of Pet Product News International. “But this old news is a tack that depends on the success of upper-echelon, higher-income, better-educated consumers able to understand and afford the nuances of themes such as ‘ancestral.’ Only about 10% of pet shoppers fall into a decidedly affluent category, so with its tenure this strategy is now largely one of robbing Peter to pay Paul rather than creating real market growth.”

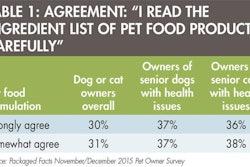

Lummis’ colleague, David Sprinkle, research director for Packaged Facts, has also pointed out that even people who consider themselves “pet pamperers” disproportionately demand higher quality in pet foods and products without necessarily being willing to pay more. “Among those consumers who strongly agree that their pet is part of the family, 44% strongly agree that they look out for lower prices, special offers and sales on pet products,” Sprinkle wrote.

This attitude among even the most devoted pet parents is at least partially due to what Packaged Facts calls the “new normal economy,” which has turned even affluent consumers into lifelong value-minded shoppers. And, it’s worth noting that today’s most affluent consumers—and pet owners—tend to be Baby Boomers. As they grow older, at least some might follow the traditional trend of falling out of the ranks of pet ownership. While newer groups of pet owners are emerging, notably among Millennials and Hispanics, they may not be as able or willing to shell out big bucks for premium or superpremium pet foods.

Seth Mendelson, group publisher and editorial director for Pet Business, addressed the changing demographics of pet ownership, writing that we may have “reached a brick wall in terms of raising pet food prices. The last thing the industry wants to do is make potential pet owners question whether they can afford an animal in their home.” He also cautioned that existing pet owners might push back against escalating prices, “ready to draw a line in the sand. If that happens, it could just mean that they will look for lower-priced alternatives. Or they may say that pet ownership is no longer in the family budget.”

Premium pet food: in search of meaning

The answer to these concerns, as the Pet Business article suggested, is to better explain what premium and superpremium products are and why they offer robust, healthy nutrition for pets and good value for their owners. To date, that has not proven an easy or straightforward task.

In older reports, such as its Pet Food in the US, 9th Edition (2011), Packaged Facts attempted to define the premium and superpremium terms: the former was for products priced 10-20% above the category average, while superpremium products were priced 20% or more above the average. It’s difficult to know whether those definitions still apply; even Packaged Facts doesn’t seem to use them anymore.

In her article, Brewer asked several pet food company representatives and pet retailers how they defined the terms and, as could be expected, the responses were all over the map. She also referenced an unnamed representative of the Pet Food Committee of the Association of American Feed Control Officials, who said the terms “indicate what a manufacturer thinks they mean or wants consumers to think they mean.”

Indeed; good luck getting even a handful of manufacturers or marketers to agree on definitions. And I doubt that anyone realistically believes that regulations are the best way to define the terms, especially if they don’t appear as claims on pet food labels.

So, the best option seems to be for pet food companies to make the strongest case possible, as clearly as possible, for why their products cost what they do—not only to pet food shoppers but also, perhaps more importantly, to pet retailers who bear a cost for stocking the products and are the ones directly interacting with consumers. Is it too much to ask that, in making their case, companies do so honestly and transparently, without bad-mouthing their competition? Our industry’s survival may depend on it.